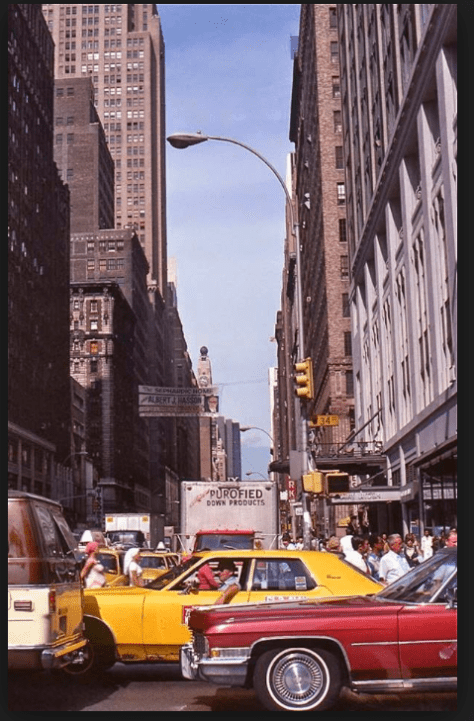

It was a cool, crisp, late Fall afternoon in The City in 1976 and I had been driving a cab at night through the mean streets for about a year.

It was a cool, crisp, late Fall afternoon in The City in 1976 and I had been driving a cab at night through the mean streets for about a year.

I had always liked to drive and considered myself quite good at it. When you drive the same car an average of 125 miles each night, night after night, through the streets of New York for a year, it becomes an extention of your body. I had a good body then. I was 29, six feet tall, I weighed about 165 pounds and I didn’t take any shit from other men.

I was armed with an aluminum lunch box with a turkey sandwich with sprouts in a plastic bag and on the front seat next to me I carried a green apple wrapped like a hand-grenade in a paper towel that Shirley, my girlfriend at the time, had packed for me. Next to my lunch was my old wooden cigar box with a five-dollar bill and eight ones. Hanging on a steel strap next to the taximeter was my metal coin changer. It would make a decent substitute for a pair of brass knuckles should I need to defend myself against an attacker, although I would imagine that the impact against his grizzled face would have cost me a few lost quarters if not a few dimes and nickels. On my size 13 feet, I still wore my old black combat boots which had been the only things I had taken with me when I got out of the army several years before, other than a few vague notions of what my life as an artist might be like after I moved to New York. Back then, I never imagined myself as a cab driver.

Sixty-ninth Street between Central Park and Columbus is a one way street running West. And there are always parked cars lining both sides of the street. At times, there are even cars double-parked on both sides of the street– leaving only enough room for one car to squeeze through. I prided myself on my skill behind the wheel. I could run the gauntlet across Sixty-ninth street at 30 miles an hour with inches to spare on either side. Passengers would sometimes comment or, more often I would glance in the rear-view mirror to see them cowering on the back seat of my cab with their teeth clenched and their eyes squeezed tightly shut. Once I even thought I heard a man praying.

That was then.

But now, I was in Lower Manhattan in the 20’s driving up the center lane of Third Avenue in search of a fare. There were cars and other cabs on either side of me and we were hurtling uptown in a yellow wave at thirty or thirty-five, timing it so as to catch all the green lights as we went. As I drove right up to the edge of recklessness, my eyes scanned either side of the Avenue and I positioned my taxicab so as to be the first one to be able to pull over to the left or the right should anyone be foolish enough to step out into the street from between parked cars to hail me.

Blowing past Twenty-third Street at forty miles an hour, I was in the lead of a group of cabs all jockeying for position. Block after block rushed by in a blur by as we all raced foward in search of a fare. Suddenly I noticed one of the cars speeding along in competition with me to my right. To my surprise, it wasn’t a Checker or a yellow cab or even a gypsy cab. It was a little maroon-colored car.

What kind of idiot drives a little maroon-colored car at forty-five miles per hour on a busy city street?

Whatever kind of idiot does, was behind the wheel and seemed to be in a big hurry to get wherever he was going and I watched in annoyance as he weaved in and out of traffic and kept pace with me. The nerve. I’d show that maroon who was the boss of the streets.

And so, I forgot all about fares and picking up people and making money.

Someone should let that moron in the maroon car know that it was dangerous to drive that way in New York City.

I decided that person should be me.

I quickly angled my taxicab over to the right with the intention of pulling up next to them and giving them some nice, friendly, helpful advice.

New Yorkers should help each other.

Instead, they sped up, so I sped up– and suddenly we were shooting uptown passing a few people who tried to hail me. I was rapidly approaching the edge of my comfort zone, so I made the determination that the best course of action would be to force the offending driver to come to a stop.

I pulled right along side of them and the driver looked at me. He actually looked surprised to see me, but kept driving. He was in the right hand lane and there were cars parked all along Third Avenue. I stayed parallel to him blocking him from changing lanes so that eventually he was forced to come to a dead stop when he came to a bus that was picking up passengers in the right hand lane.

I pulled up a little ahead of him, stopped my taxicab and got out.

As I walked back toward his car, I could see that there were two men in the car. I walked over to the driver’s window and offered the man behind the wheel the following helpful advice: “If you want to kill yourself, get a gun.”

The passenger door of the little maroon-colored car opened and the passenger got out and approached me.

He was a large man of Asian descent. He reminded me vaguely of a villain in a James Bond movie I had seen once, years earlier. He was about four or five inches taller than I was and outweighed me by about fifty pounds. Suddenly I felt very small and very stupid. He addressed me:

“You got a gun, cab driver…?”

I tried to think of something tough and clever to say but I drew a blank. Besides, it didn’t seem like the kind of question where the asker expected an answer. It was more of a rhetorical question. So I just stood there, staring into his thick hooded eyes, and trying not to pee in my pants.

After a few more seconds, he said, “Get back into your cab and drive, taxi driver.”

Seemed like good advice to me.

And very helpful.

Many years ago, before cellphones, in an age when ordinary people walked the streets of the big city in silence, lost in their own thoughts– or for those like me, hopelessly lost in dreams, there was a company called Marvel Comics on Madison Avenue.

Many years ago, before cellphones, in an age when ordinary people walked the streets of the big city in silence, lost in their own thoughts– or for those like me, hopelessly lost in dreams, there was a company called Marvel Comics on Madison Avenue.