After returning home from a month in summer camp in North Carolina, when I was still only twelve, I fell in with a small group of younger kids from down the street. We would all randomly congregate at a small circular park at the end of the block, known as “The Circle”.

On The Circle’s west side was a small, mysterious, but otherwise unremarkable brick building, which I later found out was a “pumping station”—whether for water or sewage, I never knew, although there was plenty of each in my home town.

I found out about 40 years later when they were digging up the street that there were some very large pipes which ran under the street to this building, although I doubt any of us knew it at the time. From time to time, one could hear mysterious whooshing sounds coming from inside the windowless building, too, as if the unoccupied windowless brick building was constructed to obscure some ancient magical waterfall.

There were plenty of big bushes, too, some with little orange berries that were good for throwing at other kids, three or four magnolia trees, at various locations in the park, suitable for climbing, and one open area large enough to get up a game of “half rubber”, a bastardization of baseball involving a solid rubber ball cut in half and a sawed-off old broom handle for a bat. One nice thing about half rubber was that you only needed three players—a pitcher, a batter and a catcher—although an outfielder would have been nice.

There was also an open area on the South side of The Circle which was large enough for tackle football, where there was a small patch of bare earth where the grass had been worn away, mute testimony to the spot where most of the main action had taken place.

“Solomon Park”, as it was known on the maps, was situated on a side street, so there wasn’t much car traffic, which made it an ideal place to play or to circumnavigate on a bicycle.

In those days every kid over the age of five or six had a bicycle, and as far as I knew, was free to roam the neighborhood with no adult supervision, as most kid’s fathers were at work and their mothers were home taking care of smaller children or tending to household responsibilities.

I never once saw an adult in that park.

Anyway, it became a thing that August to see which of us “big kids” could ride his bicycle around the park the most times. It took about two and a half minutes to circle the park on a bike. There were three or four kids aside from myself who showed up there, day after day, at the end of that summer.

Hour upon hot hour, we would ride around and around, each kid keeping track of the number of revolutions he had made.

There were no girls in our group. Boys like us didn’t play with girls. I considered it traitorous.

It was an unusually hot summer that year and a couple of the younger boys had taken to throwing cups of water on us each time we came around. Most kids in those days rode American bicycles with big rubber tires, but I had a red “Rudge”, an English bike with thin tires and two hand brakes.

I had gotten it for Christmas when I was six and been riding it for half of my life at this point.

On days I was not in school, I was allowed to sleep late, and in the summertime, my parents were both at work by the time I woke up. At this time of the morning, the only other person at home was my grandmother, an “invalid”, who by this time of the morning, would have pulled herself up out of bed, using a makeshift “trapeze” of two by fours, sawed-off broom handles and doubled-up clothesline rope my Dad had rigged up for her, and plunked herself down in her wheelchair for another day.

She was like a mother to me and spent her day looking out the window at the birds and squirrels or reading her bible, or making phonecalls for the Calvary Baptist Church or writing letters to her son in Washington, D.C. She talked to “Tweety” and “Pete”, her two parakeets.

My mother told me that parrots and parakeets could “talk”, so I was sure they understood her every word, and one day would answer back, but they never did.

My grandmother, whose name was the same as my own mother’s, had a small black and white television set on a rolling tubular aluminum stand in one corner of the room and she spent her time watching quiz shows like The Price Is Right (with Bill Cullen), where contestants tried to guess the price of common household items without going over the price, or “Kids Say The Darndest Things” with Art Linkletter. She crocheted booties, bonnets and bedspreads for her 8 grandchildren and any others who asked.

It was great for me to have her there all the time, but she was in no condition to ever stop me from going wherever I wanted–and besides, I never asked anyone’s permission, because for the most part, being of an impulsive nature, I never knew where I was going until I was on my bike headed there. My Grandmother never knew where I was or what I was doing when I was out of the house, which was a good deal of the time. And if she had tried to stop me, I would have not listened to her.

Monday, August 31, 1959 dawned hot and the Blue Jays were restless in the magnolia tree outside my bedroom window.

It was my 13th birthday. I got an early start, and was the first one at The Circle that day. I began riding around and around, keeping count of how many revolutions I had made. By the time, I was up to about thirty, I was joined by one or to other kids and then later on, another, and we rode around and around, as the hot morning turned into the hot afternoon.

We rode silently and with determination into the late Georgia Summer.

By two or three o’clock I was up to about 150 revolutions and someone’s little brother who had joined us for a while, but dropped out, was now filling up a waxpaper Dixie cup with little green hearts on it from a neighbor’s garden hose and running over to throw water in the face of any big kid he could.

I was a teenager now, a couple of years older than the other kids and I was determined not to let anyone younger “beat me”. So I kept going, skipping lunch and not bothering to stop to go to the bathroom.

The afternoon came and went, and the sun dropped down warm and orange behind some tall pine trees in the backyard of a nearby house. Most kids had now dropped out or joined the water brigade.

I kept going.

My parents got home from work after 6, but by that time, I was still going strong. I could have kept going until after dark, but 256 times around the park was a record and that was good enough for me. The other kids had all gone home anyway.

There was no one left to impress except myself. There never was.

The next day I showed up again at the park. There were a few kids there already. They asked me how many times I went around. I told them. Someone figured out that I had ridden over 40 miles. I knew at that moment I was ready for an even greater challenge.

I would ride my bicycle to the “Dixie Jungle” in next county, to buy fireworks. It was 17 miles away. I would save my strength and my money for a month or so, and then just get up early one morning and go.

I rode home.

I was a boy with a plan.

That fall, on a sunny day in November, when the air in Georgia is crisp and cool, but not cold, with twelve dollars in my pocket and both of my parents at work and my grandmother in her wheelchair in her bedroom, I got dressed, grabbed an army surplus canvas bag to carry the fireworks in, slung it over the handlebars and slipped unseen and unnoticed, except perhaps by a stray cat out the front door of our house.

I mounted my red bicycle and carefully pedaled west on 51st Street, passing the houses of kids I knew– and kids I didn’t.

I crossed Harmon Street glancing over briefly at Solomon Park, scene of my recent triumph. I crossed Paulsen Street, where my mother always turned right to go to work.

I kept going, passing houses on whose porches I had trick-or-treated or sold Oatmeal Cookies.

I came to Habersham Street. I crossed it and rode on.

Now and then a car would pass or someone would be walking on the sidewalk. I ignored them. They returned the favor. I was invisible now with secrets to confess.

I came to Abercorn Street, a busy street leading downtown with a median in the middle of it. Years later my parents would be involved in a serious automoible accident there following an aborted attempt to flee a hurricane.

But I easily crossed Abercorn and headed West.

It was late Fall, the trees were bare and I could see the water tower at the end of the street at the Neal Blun Lumber Company. I had been down this street many times in past years as it was the shortest route from our house to Highway 17, the main highway to Florida. The main difference, was every other time I had gone this way, I had been in a car with my father driving, and we were on our way to Jacksonville to visit his mother.

This time, however, I was on my bike and all alone.

I came to the end of 51st Street and crossed the railroad tracks. Soon I was peddling past motels and gas stations on the outskirts of town. The sky was blue and I kept thinking about what kind of fireworks I was going to buy when I got to The Dixie Jungle.

I had been there before once or twice with my father. It was basically a gas station and souvenir shop selling soft drinks, chips, candy, and cigarettes, in addition to firecrackers, cherry bombs, TNT’s, Torpedoes, Cracker Balls, Skyrockets, 2-inch salutes and buzz bombs. They also had a really crummy “zoo” out back with a few monkeys, a ratty-looking bobcat, a skunk, a possum, a few bored-looking raccoons, a pony, a few chickens and a goat or two.

For 50 cents, the proprietor would take you on a brief walking tour of his sad collection of chicken-wire cages. The star of the show was “Maude The Singing Jackass,” who was advertised on hand-painted signs for miles in either direction. Maude was tied to the stump of a nearby tree and apparently didn’t feel much like singing the day my Dad took me there.

After another fifteen or twenty minutes I was really out on the highway. It was a two lane paved black asphalt road with one lane in either direction. I stayed over to the right and kept the front tire of my bike a few inches in from the edge. I was going about 15 mph and there was plenty of room for cars to pass. It was the trucks I was worried about.

I kept glancing back over my shoulder about every ten seconds and if there was a truck coming up behind me I would get off the road completely and ride slowly along the grassy median trying to avoid broken bottles or cans and then get back up on the road and continue on. There wasn’t that much traffic in those days, but, nevertheless, I had to do this many times. I passed Mammy’s Kitchen, a Bar-B-Q restaurant off to the side of the road. There was a big colorful painted roadsign of “Mammy” complete with a white bandana on her head and red and white apron. Mammy looked a lot like Aunt Jemima. I pedaled on.

I came to the bend in the road where my father had told me he had once run off the road into a ditch in 1927, when he first came to Savannah. I passed the Wise Owl Potato Chip Sign. It was cut out to the shape of a big owl and stuck up from the center of a large bush. It advised passing motorists to “Get Wise.” It seemed much larger to me now than on the many times I had seen it when my father and I were going to see my grandma in Florida. I got a good look at it. I liked that owl. I fancied that it approved of what I was doing.

At any rate, it was too late to turn back now.

When I got to the abandoned gas station with Donald Duck and Goofy painted on the inside glass window I stopped to rest. This landmark, too, I had seen it many times in the past. This time I noticed that the paintings of Goofy and Donald seemed “off” somehow. I suppose that being an artist, myself, I couldn’t help having a more critical eye than most. I sat by the side of the road and thought about Donald and Goofy and watched the passing cars and trucks for a few minutes. I imagined that Donald and Goofy approved of what I was doing.

Then I got back on my bike for the final leg of the journey.

It wasn’t long before I passed another landmark, The Bamboo Farm, and then I came into a large open area where the road passed through a marshy area. Off in the distance I could see the low open concrete bridge that crossed the Ogeechee River and separated Chatham country from Bryan County and which separated me from fireworks.

I pedaled a bit harder.

Once over the bridge and the black water, I came to a series of road signs advertising The Dixie Jungle and Fireworks.

I was almost there.

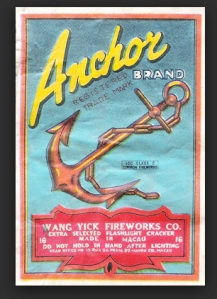

In a couple of minutes I pulled up and leaned my bike against the side of the building. It was a quiet at the jungle that day. I swung open a screen door and stepped inside. It was dark and cool and the only light seemed to be from a naked lightbulb hanging from the wooden ceiling near the center of the store. There was a man in the back of the place who noticed me when I came in, but didn’t pay me much mind, so I casually drifted over to the section where they had the fireworks for sale. I was the only customer there at the time. They certainly had a great selection. I tried not to wet myself. It would be difficult to choose between the bewildering assortment of colorful packages all wrapped in cellophane with such labels as Black Cat, Alligator, Zebra, Yankee Boy, Dixie Boy, Anchor, Camel and Cock brand, but I eventually settled on a large package containing 80 packs of Anchor Brand Firecrackers for four dollars.

I brought this up to the man in the back of the store and for good measure and because I still had a few dollars left purchased some bottle rockets and a dozen cherry bombs. Expecting to be arrested at any moment, I handed over the money and he handed me a paper bag full of power and self-respect.

I walked directly out the front door, did not pass go or collect two hundred dollars.

I placed the goodies in the canvas bag, slung it over the handlebars and started for home. I don’t remember much about the trip back, except that I arrived back home, by 1 o’clock in the afternoon.

No one had missed me.

My parents never knew what I had done and I wasn’t about to tell anyone. I went back inside and put the fireworks in a small black suitcase in my bedroom closet, where they stayed until I went to visit my cousin in Florida for New Year’s.

It’s interesting how you challenged yourself, proved something to yourself. And you certainly did have a thing about fire works!

LikeLike